“The water in Rupert is boiling, rough water and that’s just by the dock… It’s vicious that water, just vicious.” — Pat Campbell

Before and since my 2015 R2AK = Race Towards Alaska, I’ve enjoyed reading novels and non-fiction that take place along the race route: the coasts of Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska. While my favorite is still Ivan Doig’s “Sea Runners” (inspiration for our team name), the most recent good read was John Valliant’s “The Golden Spruce” in which the main character attempts to kayak from Prince Rupert across Hecate Strait to Haida Gwaii — in February. The question of whether he perished in the process, or staged an accident and disappeared into the woods beyond Ketchikan is an intriguing one, but what caught my #R2AK-eye was the author’s description of the oceanography of Hecate Strait and Dixon Entrance.

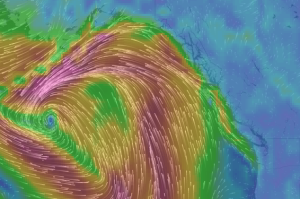

…Hecate Strait is arguably the most dangerous body of water on the coast. The strait is a malevolent weather factory; on a regular basis its unique combination of wind, tide, shoals, and shallows produces a kind of destructive synergy that has few parallels elsewhere in nature. From the northeast come katabatic winds generated by cold air rushing down from the mountains and funnelling, wind-tunnel style, through the region’s many fjords, the largest of these being Portland Inlet, which empties into the strait 50 km north of Prince Rupert. Winter storms, meanwhile are generally driven by Arctic low pressure systems born over Alaska, and they tend to manifest themselves as southerlies along the coast. It is because of these winds that the weather buoy at the south end of Hecate Strait has registered waves over 30 meters high. One of the things that makes the strait so dangerous is that these two opposing weather systems can occur simultaneously. Thus, when a southwesterly sea storm, blowing at 80 – 160 km/hr collides, head-on, with a northesasterly katabatic wind blowing at similar strength, the result is a kind of atmospheric hammer-and-anvil effect. Veteran North Coast kayakers tell stories of winds like this lifting 180 kg of boat and paddler completely out of the water and heaving them through the air.

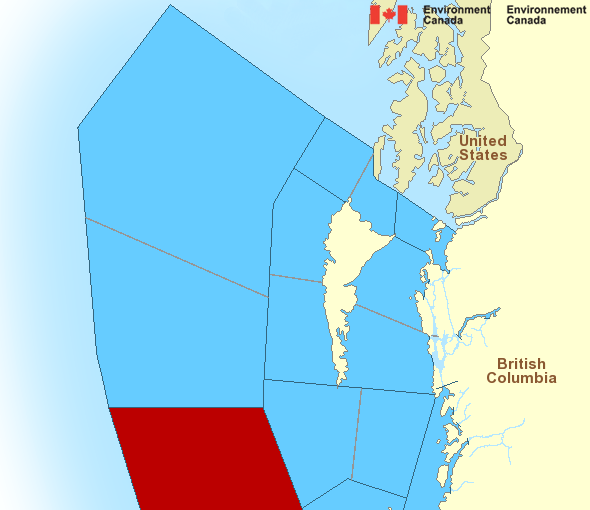

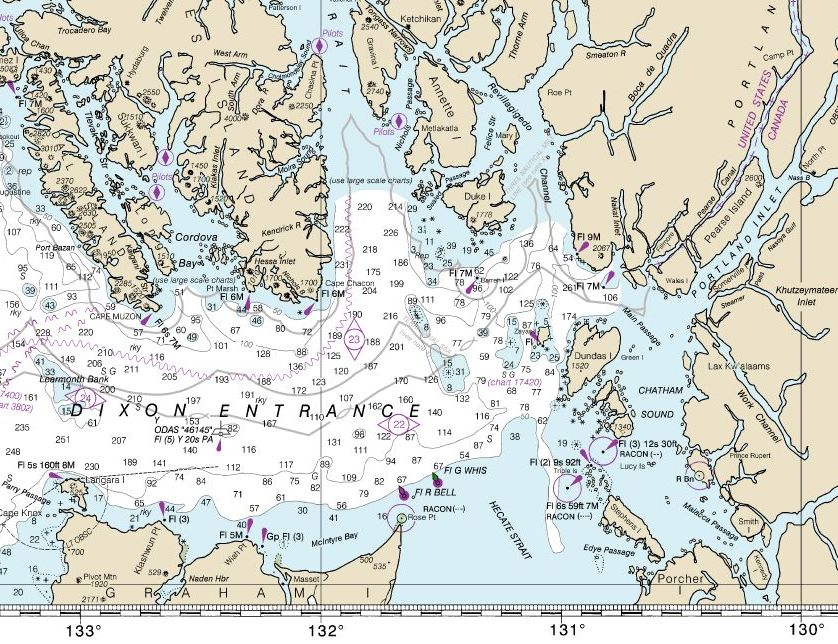

NOAA chart showing Prince Rupert, Masset, and Ketchikan.

NOAA chart showing Prince Rupert, Masset, and Ketchikan.

But this is only one ingredient in Hecate Strait’s chaos formula. Tides are another; in this area they run to 7 meters, which means that twice each day vast quantities of water are being pumped in and out of the coast’s maze of inlets, fjords, and channels. The transfer of such volumes in the open ocean is a relatively orderly process, but when it occurs within a confined area like Hecate Strait that is not only narrow but shallow, the effect is of a giant thumb being pressed over the end of an even larger garden hose. The scientific name for this is the Venturi effect, and the result is dramatic increase in pressure and flow. A third ingredient is a frightening thing called an overfall which occurs when wind and tide are moving rapidly in opposite directions. Overfalls are steep, closely packed, unpredictable waves capable — even a modest height of 4-5 meters — of rolling a fishing boat an driving it into the sea bottom. They can show up anywhere but their effects are intensified by sandbars and shoals like the one that extends for 30 km off the end of Rose Spit between Masset and Prince Rupert. Under certain conditions, overfalls take the form of “blind rollers,” which are large, nearly vertical waves that roll without breaking; not only are these waves virtually silent, but under poor light conditions they are also invisible — until you are inside them. If one then factors in the prevailing deep-sea swell that in winter surges eastward through Dixon Entrance at heights of 10-20 meters, and the fact that a large enough wave will expose the sea floor of Hecate Strait , the result is one of the most diabolically hostile environments that wind , sea, and land are capable of conjuring up.