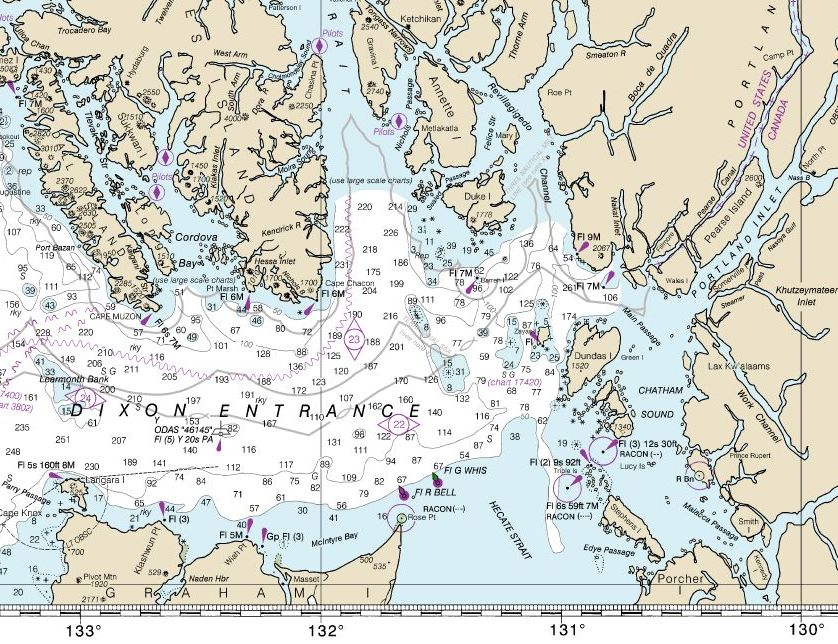

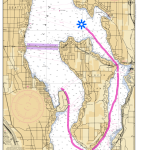

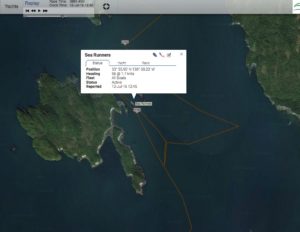

The Race to Alaska is a big race. There are many uncertainties and it’s complicated. As simple as the rules are — no motors, no outside support and no crew changes; go from Port Townsend to Ketchikan stopping in Victoria to clear Canadian Customs and then transit Seymour Narrows and sail past Bella Bella — the waters that the race crosses are wild and varied: fickle winds in the Strait of Georgia; raging currents of up to 16 knots at Seymour; soul-sucking rain possibilities on the north coast; water-jet like winds funneling out of mountain inlets with little notice; and endless rocks and other obstacles to hit.

How do you prepare for this maelstrom of conditions in what is essentially a desolate inshore race?

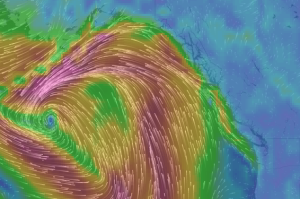

Though the race was conceived of in the United States by American organizers, all but about 75 miles of it is in Canada. As the 2015 race proved, the weather along the B.C. coast governed the race. Some teams got lucky and rocketed north enjoying a nice summer sail. Others had their hopes dashed as they fought vicious conditions that were possible but unprecedented. Environment Canada, has many responsibilities — from trying to understand the chimera that is climate change to enforcing rules related to boundary waters like the Northwest Passage. In the midst of all this they are also expected to predict what the weather will be like in a few short passages. The Canadian weather forecasting body in their publication Nation Marine Weather Guide: British Columbia Regional Guide go on for 152 pages about the hazards of the B.C. coast. They provide helpful mariner antidotes such as “The day before a major southeast storm is often deceptively calm; then the bad weather strikes with a vengeance. Veteran mariners call these glassy calm days “weather breeders.”” But most foreboding are deadpan statements delivered in a calm bureaucratic voice from afar like: “Several locations across the Georgia Basin appear to experience significant changes in their wind and weather patterns—Seymour Narrows, in Desolation Sound, being one of them. It is said that going north through Seymour Narrows and the Yuculta Rapids is like going through a door into another room, with both colder water and air. Precipitation amounts are also different on opposite side of the Narrows.” That should make you realize that this is not going to be an easy race.

Though the race was conceived of in the United States by American organizers, all but about 75 miles of it is in Canada. As the 2015 race proved, the weather along the B.C. coast governed the race. Some teams got lucky and rocketed north enjoying a nice summer sail. Others had their hopes dashed as they fought vicious conditions that were possible but unprecedented. Environment Canada, has many responsibilities — from trying to understand the chimera that is climate change to enforcing rules related to boundary waters like the Northwest Passage. In the midst of all this they are also expected to predict what the weather will be like in a few short passages. The Canadian weather forecasting body in their publication Nation Marine Weather Guide: British Columbia Regional Guide go on for 152 pages about the hazards of the B.C. coast. They provide helpful mariner antidotes such as “The day before a major southeast storm is often deceptively calm; then the bad weather strikes with a vengeance. Veteran mariners call these glassy calm days “weather breeders.”” But most foreboding are deadpan statements delivered in a calm bureaucratic voice from afar like: “Several locations across the Georgia Basin appear to experience significant changes in their wind and weather patterns—Seymour Narrows, in Desolation Sound, being one of them. It is said that going north through Seymour Narrows and the Yuculta Rapids is like going through a door into another room, with both colder water and air. Precipitation amounts are also different on opposite side of the Narrows.” That should make you realize that this is not going to be an easy race.

So how do you prepare? You need a list, but this is no “I’m going to the grocery store, what do we need” kind of list! First you need to be really hungry (or even insane or obsessed?) to even want to contemplate “going to the store.” But yes, you do need a list:

1. Boat

2. Crew

3. Food

4. Navigation

5. Safety

6. Clothing

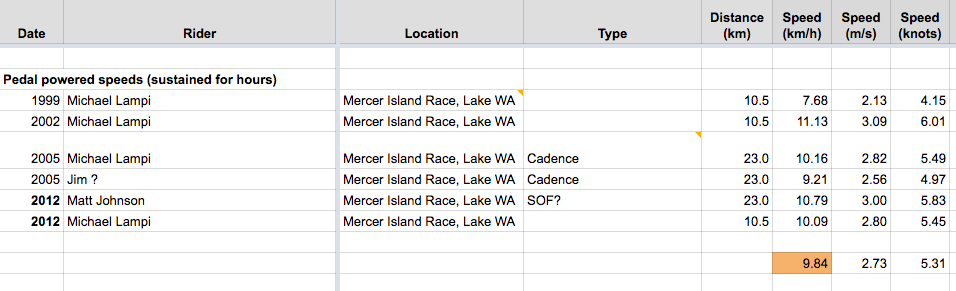

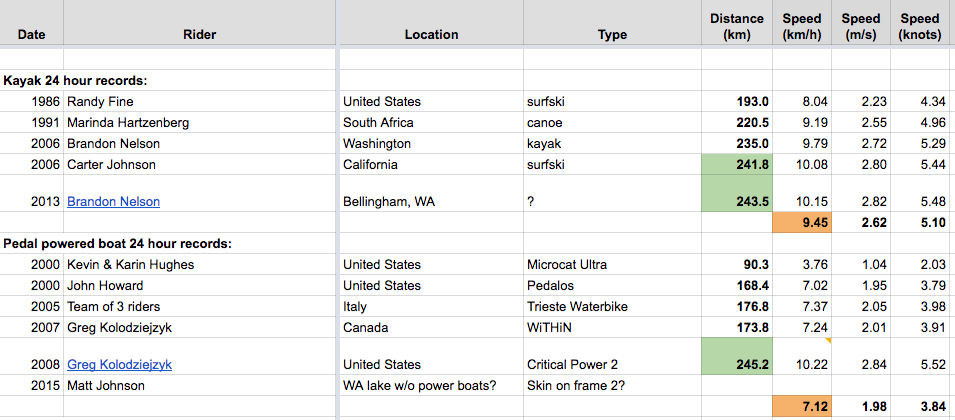

7. Human Power

8. Power

9. Water

10. Training

Easy right? It’s only 10 items. Perfect! But doubt creeps in like a day-long fog. Within those 10 items you can obsess about the perfect sub-list — each category breaking down into hundreds of sub-items each with their doubts and flaws. And it is easy to go down the rabbit hole each item generates and completely forget the others.

In the end, this race, conceived as a opportunity for six sets of local friends to row-sail their open boats up the coast as a lark, has quickly become a somewhat predictable battle and something of the money race. This of course was an invited outcome. You don’t challenge Larry Ellison of America’s Cup stature to show up in an America’s Cup boat without other like minded individuals taking up the call. Don’t get me wrong. It will be entertaining to watch a stand-up paddle boarder challenge a mega-trimaran. The odds are as endless as is the difference in the list of what to bring. As one racer commented to another on Facebook recently when the second individual stated they were planning for a two-week transit, “I thought this was a race.” The perspective on this event varies greatly. Last year’s record of five days, one hour and 55 minutes stands as the World Record. It’s a challenge that in its audacity says “go ahead see if you can break me!” What bad choices might be made because of this worm dangling on a hook? Contemplating pushing the limits of yourself and/or boat leads to more list obsessions…

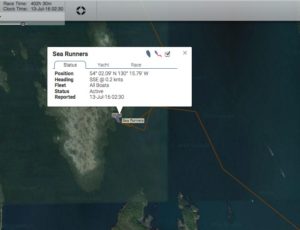

Why even enter? The prize seems hardly worth it as it will likely cost more to enter than the ten grand nailed to a tree you’ll win if you’re the first boat in. And if we “know” that a big, monied, multi-hull with a super-crew onboard is going to win then why even do it? Well, there is a slight chance that they won’t win and you might. There is also the internal race, the one we all have with ourselves if we are even half awake. And there is the camaraderie of talking boat with like-minded souls with a dash of safety net thrown in (thanks SPOT!).

As they contemplate their motivations, there are many other questions faced by racers. The curious and the casual refrain from asking “Why the hell are you doing this?” Instead they want to know the mundane. “How will you sleep?” “What are you going to eat?” And the one complete strangers want intimate details about: “How will you poop?”

Perhaps inside we all know why we attempt these type of endeavors but are afraid of the consequences of listening to the voice within. Regardless of these questions, it will be a challenge to the racers and entertaining to the observers.

The race starts in just over two weeks. There’s still time to obsess about the list.

#R2AK #RacetoAlaska